Downtown Jackson

Architecture Tour

Grand Opera House

This establishment was built in 1883 and originally known as Jones Music Hall, after owner Thomas M. Jones. It was the first opera house in Jackson, preceding Crescent Opera House, now the Arch & Eddies parking lot, by two years. Soon after its dedication on May 16, 1883, the Jones Music Hall housed the 7th Jackson High School graduation, which included 6 graduates. The building was also used for hosting speakers, roller skating, formal balls, and theatrical productions.

In 1892, Jones sold the building to Gershun David and Moses Sternburger for $4,300, even though the cost of construction was close to $16,000. That would be over $500,000 today. David and Sternburger extensively remodeled; the east wall was expanded, the stage was moved, and the auditorium was redecorated. They also added electric lights and heating. The theater reopened March 3, 1892 as “Grand Opera House”. Not long after, disagreements arose between David and Sternburger, and the opera house was purchased by Daniel P. Col in 1907.

Quick Facts

- Year Built: 1883

- Notable Establishments: Jones Music Hall, Grand Opera House, Coll Auto Sales

- Building features: “Jones Hall” seen at peak

Coll renovated once again. The ceiling was frescoed, and all the walls, woodwork, and metal finishes were redone. Coll also started showing silent films beginning in December 1912. Over the years, the opera house featured minstrel shows, concerts, movies, lectures, and more. The final stage production was July 16, 1937. The Players Club of Jackson performed Under the Gas Light, whose poster is still visible within the now-defunct theater. By 1948, the scenery flats and theater seats were removed.

For many years after Grand Opera House closed, the building was home to Coll Auto Sales. Now it is the site of Jackson Transportation. However, the outline of “Jones Music Hall” is still visible at the decorative point of the roof, along with “1883”, the year of construction. The building exterior includes popular architectural features of the late Victorian era. The ornamental window hoods and brackets along the eaves are staples of Italianate architecture, while the swirls and spires of the decorative roof point are influenced by the eclectic Queen Anne style.

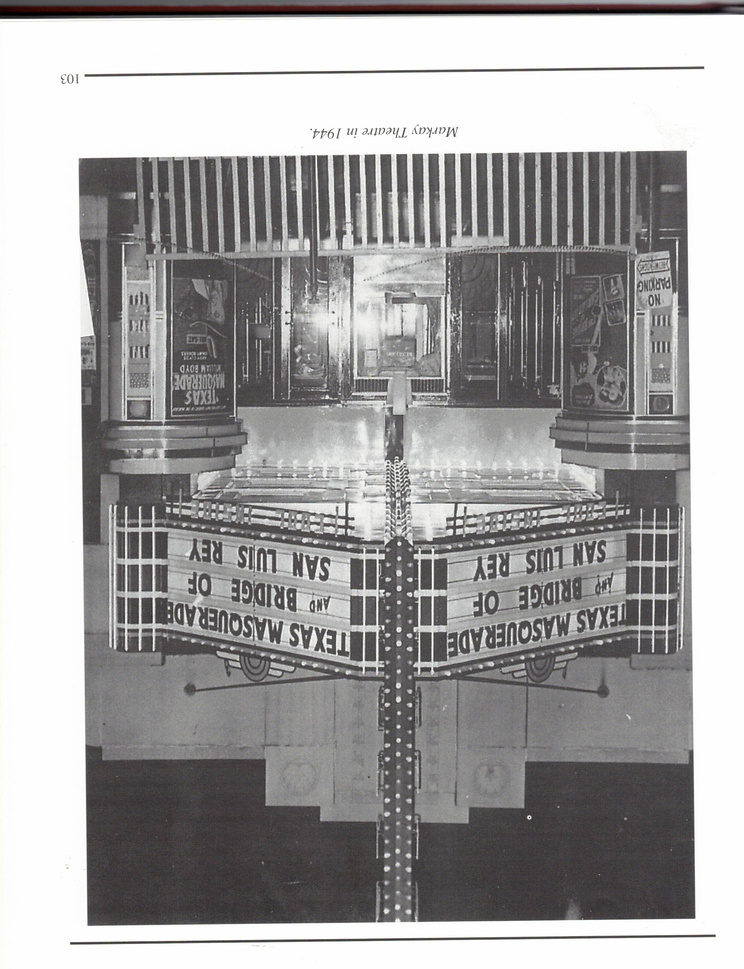

The Markay

On April 14, 1930, Earl P. Jenkins announced plans for a new theater in Jackson owned by Jackson Amusement Co. His associates were brothers Donald and Dwight Jones and Jenkins’ sister-in-law Mrs. H.M. Zweifel. Architecture firm Miller and Reeves of Columbus was hired to draw the plans for the theater. O.C. Miller was a Jackson native whose family owned the longstanding Miller’s Drug Store.

During construction, the owners strove to use local labor whenever possible. The building was built in the distinctive Art Deco style–as seen in the scalloped gables and shell details–a rarity outside of major cities, and the inside was decorated in a similarly opulent fashion. The lobby was fitted in green and gold, while the theater featured an English mosaic ceiling, leather seats, and walls paneled in red, blue, and green. Both the curtain and projector were automatic. The second floor was home to the Markay Soda Grill. In total, the initial investment was estimated to total $100,000, which would be nearly $2 million today.

A naming contest was held for the new theater in July of 1930. The winner was “MARKAY”; a combination of “Marian” and “Katherine”, the wives of Donald and Dwight Jones respectively. Opening night was October 20, 1930, and the theater showed The Playboy of Paris. Cecil B. DeMille’s The Greatest Show on Earth was shown at the Markay in 1952. The film, which won Academy Awards for Best Picture and Best Story, included a performance by Jimmy Stewart and a writing credit for Jackson native Frank Cavett.

Quick Facts

- Year Built: 1930

- Architect: Miller and Reeves

- Notable Establishments: The Markay, Southern Hills Arts Council

- Building features: Art Deco exterior, original bas relief wall decor

Jackson Amusement Co. opened a sister theater in 1938 on Broadway. The Kaymar was at the site where Sherwin-Williams is now. From 1940-1973, both the Markay and the Kaymar were leased to Chakeres Theater Co.. The Kaymar shut down in 1962, but the Markay remained open as it changed hands multiple times during the 1960s and 1970s. Sadly, the theater closed in the early 90s and was acquired by the City of Jackson in 1996.

In 1996, The Southern Hills Arts Council began renting the Markay from the city for $1 per year and started the 20-year project of renovating the historic theater. Instead of restoring the theater to its original appearance, the Council sought to salvage any possible original materials. Part of the theater was opened as The Markay Cultural Arts Center in 1997, including the lobby, which was now a Gallery to showcase local art and exhibits. Moving to the auditorium, the Council restored the six original bas-relief figures representing Jackson’s various industries. They also salvaged four floral-patterned octagonal chandeliers. Through grants, volunteer labor, and a “slow but steady” renovation strategy, the 2 million dollar project was completed with no debt. On August 1, 2015, the Markay was fully reopened for live theatrical productions and classic film showings.

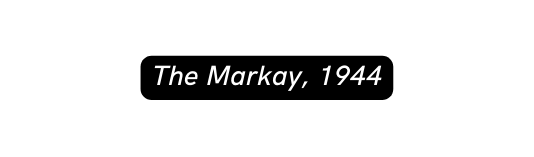

The Memorial Building

Before the Memorial Building, this was the location of the proposed Carnegie Library. In 1903, Andrew Carnegie offered $10,000 for the construction of a public library in Jackson. His stipulations included the city providing a site and passing a tax levy. Building plans were drawn by architect Frank L. Packard, who designed The Cambrian Hotel. However, Carnegie’s terms were not met and the project fell through.

During the Great Depression, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) was one of the New Deal employment programs created by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. In 1936, the WPA began constructing a gymnasium for community use in Jackson. However, when the initial cost threshold of $25,000 was removed, the City of Jackson and the American Legion contributed additional funds for the WPA to construct a “Memorial Hall” to house both city and American Legion offices. The construction utilized unemployed skilled laborers, and local materials were used to keep costs down.

WPA construction created a new subset of the Art Deco architecture movement. Known as PWA or WPA Moderne, the New Deal structures featured a simplified version of Art Deco. Designed by architect Benjamin Jones, the Memorial Building is an example of this. It has a symmetrical layout with chevron details, faux-Corinthian columns, and geometric detailing on the corners. The yellow brick is known as “buff brick”, and it is common in Eastern Ohio due to an abundance of fire clay.

Quick Facts

- Year Built: 1937

- Notable Establishments: The Memorial Building, (proposed) Carnegie Library

- Architect: Benjamin Jones

- Building features: WPA Moderne exterior

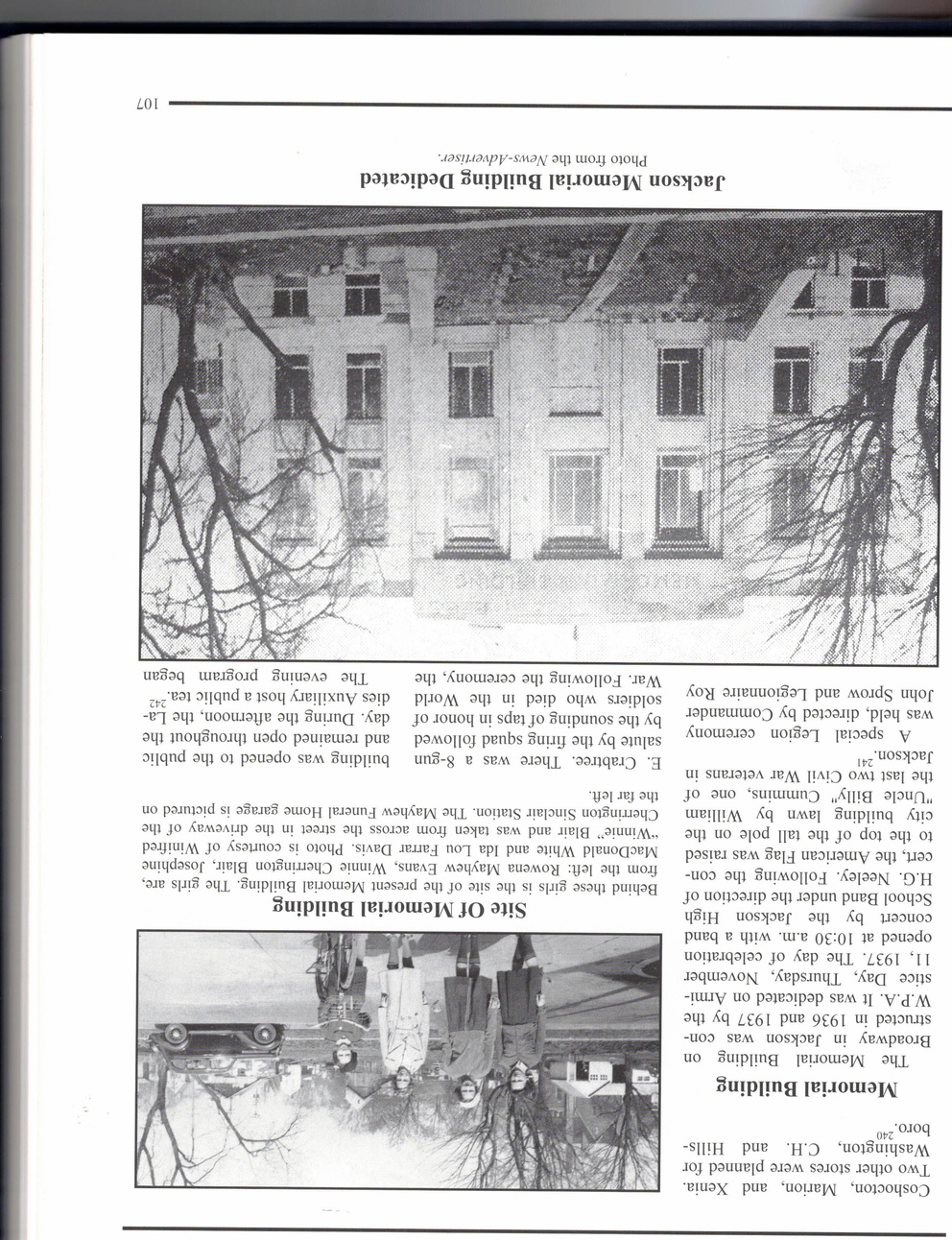

The dedication for the Memorial Building was held on Armistice Day, November 11, 1937. The ceremony featured the Jackson High School Band, an 8-gun salute, and a flag raising by one of two remaining Civil War veterans in Jackson. In 1957, a one-room addition was built on the roof for civil defense air spotters. This was likely due to the Ground Observer Corps, a Cold War-era civilian plane spotter program run by the U.S. Air Force.

The American Legion has since moved to a different location, but from 1937 to 1975, the second floor served as the home of the Jackson City Library. Today, the Memorial Building is still home to the offices of the City of Jackson, and the gymnasium benefits many groups in the community.

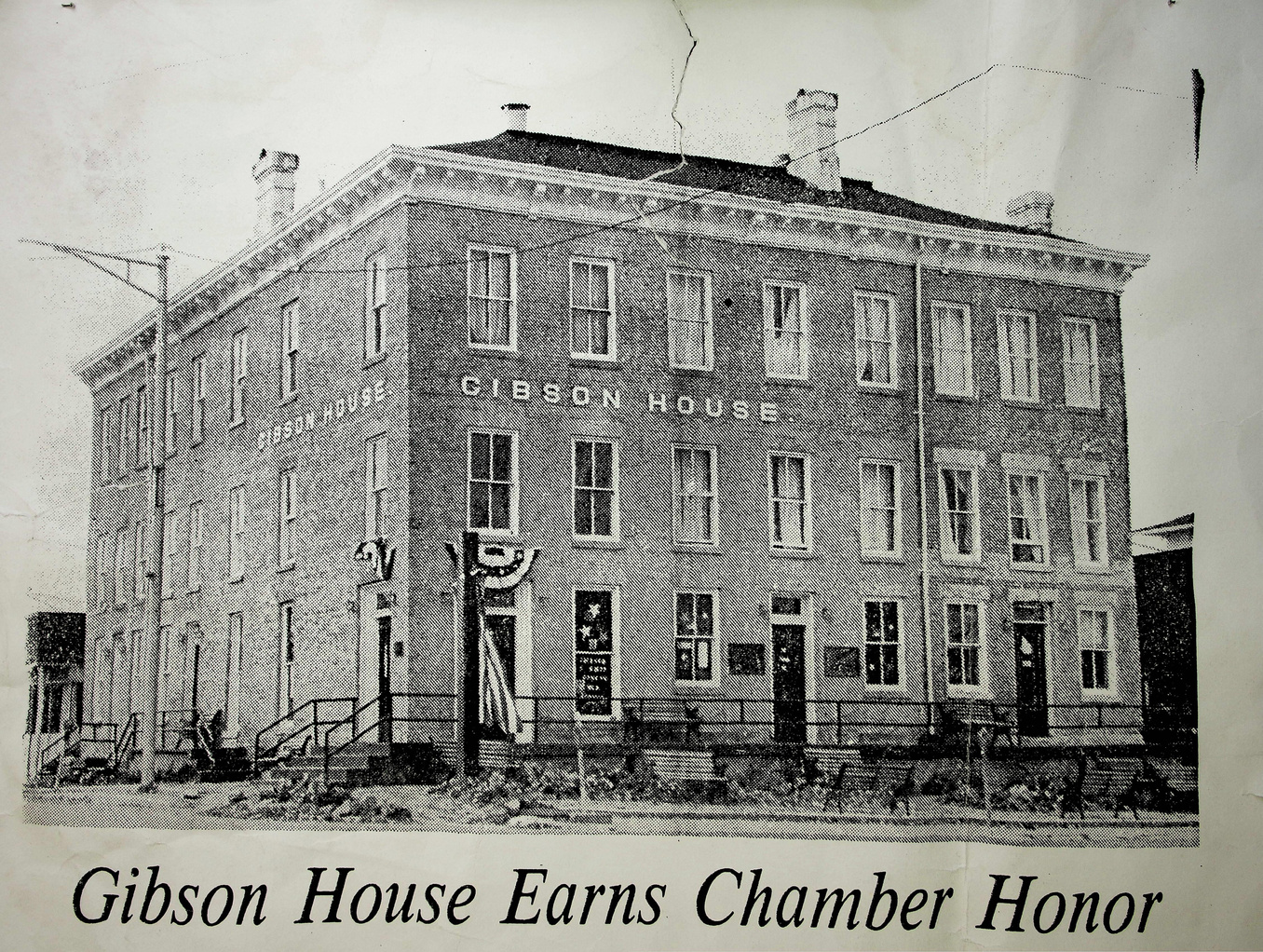

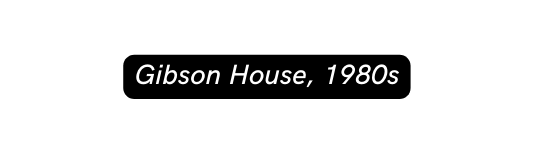

The Gibson House

Where the Veterans’ Park is now was once the site of the Gibson House. Not much is known about the construction of the hotel, but the establishment dated back to 1816. The lobby and second floor above were estimated to have been built in the 1840s when the hotel was still the property of the original owner, David Hoffman. Upon Hoffman’s death in 1861, the hotel was sold to Levi Gibson. After Morgan’s Raiders swept through Jackson in 1863, Gibson billed the State of Ohio for meals for the raiders and feed for their horses.

A large addition and a third story were added during an 1883 renovation. At that time, the Gibson House offered complimentary transportation to and from the railroad depot. Until 1915, the Gibson family continued to own the hotel. For the next decade, the hotel changed hands at least 5 times, until it was purchased by the Wick family, who also operated The Cambrian. By 1927, the Gibson House was known as the Gibson Hotel, and in 1931, the Wicks ended their contract with The Cambrian to focus on the Gibson. Around the same time, the hotel underwent an extensive interior remodel. The lobby was redone in the French provincial style. The walls were re-papered, the woodwork re-done, and all of the bedroom furnishings were replaced. An outdoor restaurant and entertainment area, known as The Summer Garden, opened May 26, 1934.

Quick Facts

- Year Built: 1840s

- Notable Establishments: The Gibson House, The Summer Garden

- Building features: Three stories, stucco exterior

- Demolished: 2006

Following the death of Wayne Wick in 1959, the hotel once again cycled through owners. David Wilkin bought the hotel in 1979, and he began the process of submitting the Gibson Hotel to the National Register of Historic Places. Also under Wilkin, the name was changed back to the Gibson House in 1983. In November of 1985, the Gibson House was officially included in the National Register of Historic Places.

Unfortunately, the hotel fell into a steep decline in the early 2000s, and the question of demolition was raised. Supposedly, a grudge match between Wilkin and the local government had resulted in Wilkin’s involuntary admittance to a mental institution and the City’s ownership of the hotel. Believing the cost of demolition could be used for repairs, the Jackson Historical Society hired a structural engineer who reported the building was in need of repair, but in no danger of collapsing. Despite the findings, in February of 2006, the Gibson House was razed. On Veterans’ Day, November 11, 2014, the location was dedicated as Veterans’ Park, with an accompanying memorial paying tribute to those from Jackson County who have served in the Armed Forces.

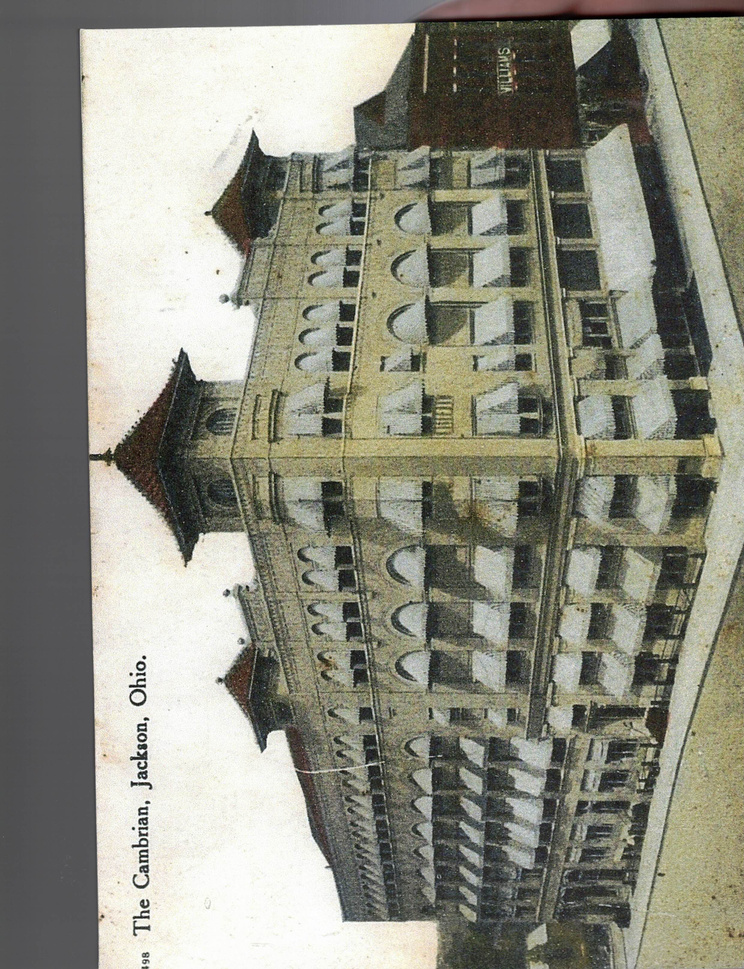

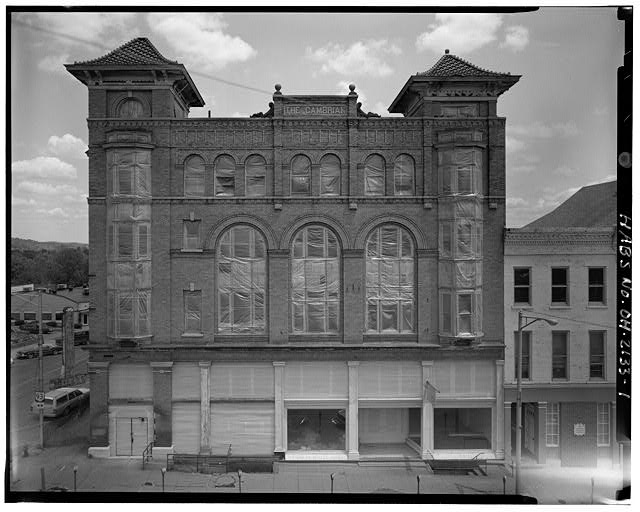

The Cambrian

The Cambrian was built by industrialist Edwin Jones, who believed Jackson deserved a grand hotel. The hotel was designed by renowned architect Frank L. Packard. Packard modeled The Cambrian after one of his earlier projects, The Chittenden Hotel in Columbus. Construction began in 1901 with the laying of the cornerstone. Inside, a lead time capsule was enclosed, whose contents included a list of recent events, a Bible, opera house programs, copper cents, and an American flag. The name “Cambrian” was chosen by Jones to honor his Welsh heritage, as “Cambria” was the Latin term for Wales. Like its inspiration, The Chittenden, The Cambrian was built in a grand Italianate style with arched windows and distinctive tiled cupolas on the roof. The opulent interior included a fountain in the lobby and mosaic flooring, most notably a depiction of a Welsh dragon holding a “Cambrian” flag.

On December 22, 1902, The Cambrian officially opened for business. Renting a premier room with a bath cost $3. Although Jones was the proprietor, he leased the hotel to various managers from 1902 to 1913. He sold it to Chicago developer George Gauntlet in 1913, before repurchasing the Cambrian in 1917. Jones sold The Cambrian to Harry Cruikshank of Columbus. From 1917 to 1918, the hotel briefly closed before reopening under new ownership. The most successful of the managers were the Wick family, who ran the Cambrian for over 20 years.

Quick Facts

- Year Built: 1901

- Architect: Frank L. Packard

- Major Renovation: 1985

- Notable Establishments: The Cambrian (Hotel), The Cambrian (Public Housing)

- Building features: Italianate style exterior, tiled cupolas on roof

In addition to the hotel, The Cambrian was home to many local businesses. It housed The Cambrian Restaurant and the Black Diamond. A barber shop, shoe repair shop, telegraph office, and real estate company all utilized the space by 1960. Meetings for the local Rotary and Lions clubs were held in the banquet room. However, the hotel had begun to decline, and owner Phillip Lakes closed the hotel in July of 1963. It was at this time that the interior was stripped of anything of potential value. The City of Jackson purchased the hotel in 1980, a shell of its former grandeur.

As the local landmark continued to deteriorate, the City began to consider demolition. However, a grant from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development provided the funds Jackson needed to save The Cambrian. The federal grant promised $2.5 million dollars to repurpose The Cambrian for low-income elderly housing. The City then transferred the property to the Jackson Metropolitan Housing Authority, which awarded the renovation bid to A.J. Stockmeister of Stockmeister Enterprises. Stockmeister had the lowest estimate of $2,923,55, which was still considerably more than the federal grant amount. However, Stockmeister personally lobbied in Washington D.C. Vice President George H.W. Bush for increased funding. Soon after, additional funds were received by the Appalachian Regional Commission.

One stipulation of the federal grant was that the renovation must be completed in under 1 year, a massive undertaking. The building was completely refitted with steel supports, and the interior was reworked to encompass 55 residential rooms and other facilities. Although they could not restore the interior, the “Cambrian” dragon mosaic was salvaged and hung on the lobby wall. Since The Cambrian was in the National Register of Historic Places, the renovation had to preserve the original outer appearance. The trademark cupolas were refitted with new lights, donated by Stockmeister Enterprises. It is also speculated that Stockmeister absorbed unexpected costs accrued by the project. On June 2, 1985, the official opening was held, less than 365 days from the start of construction. Lillian Jones, daughter of original owner Edwin Jones, cut the ceremonial ribbon.

Resources

References

Jackson County History by Bob Ervin

It’s History and its People, Since 1865, 1900-1950, 1950-2000, 2000-2017

Lillian Jones’ scrapbook

The Lillian E. Jones Museum

The Restoration of the Markay

Southern Hills Arts Council

Jackson County Recorder's Office

Photo Credits

Jackson County History by Bob Ervin

It’s History and its People, Since 1865, 1900-1950, 1950-2000, 2000-2017

The Lillian E. Jones Museum Collection

The National Archives

The Library of Congress

Paramount Pictures